Refugium, plural refugia: an area where special environmental circumstances have enabled a species or community of species to survive after extinction in surrounding areas. (dictionary.com)

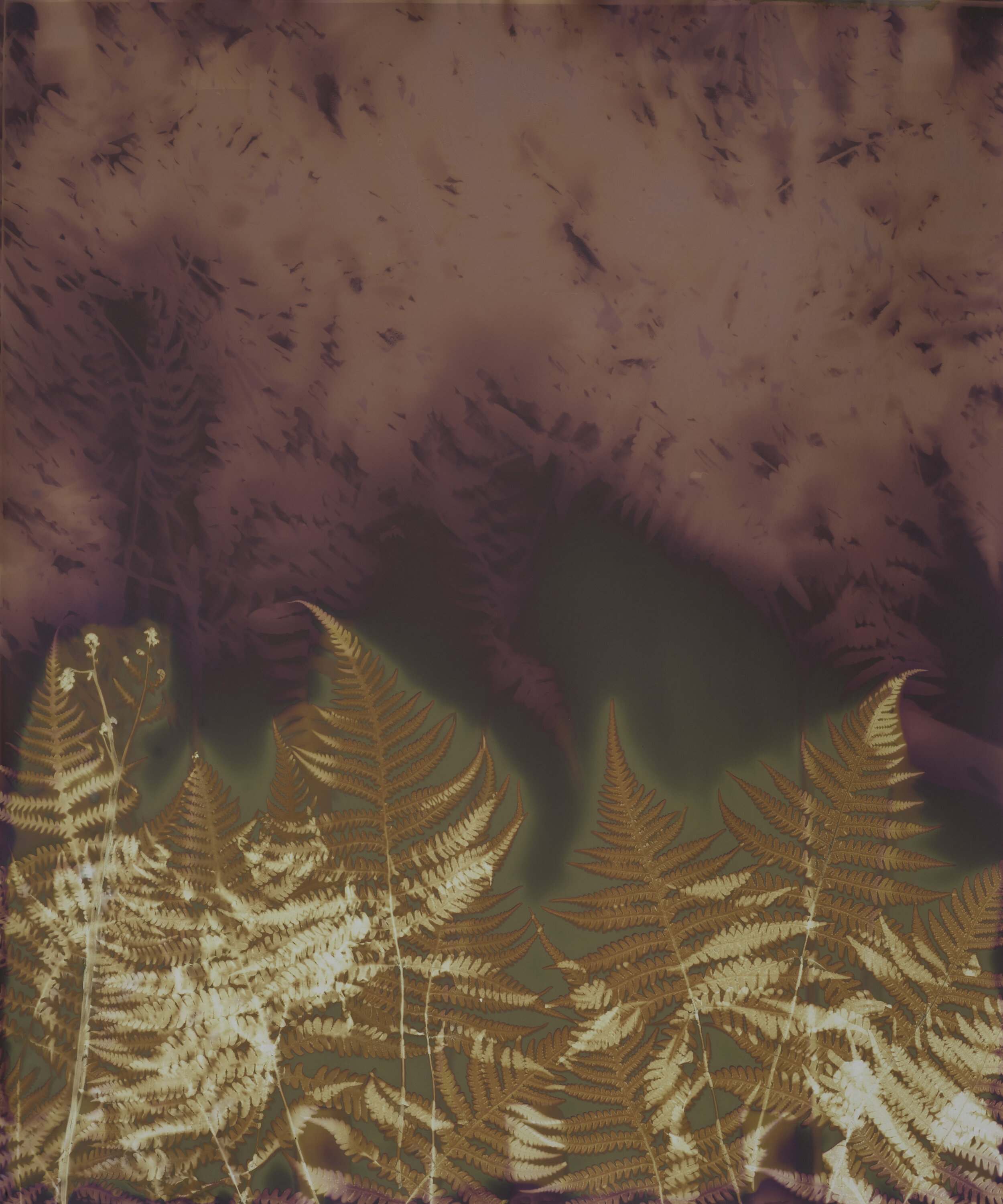

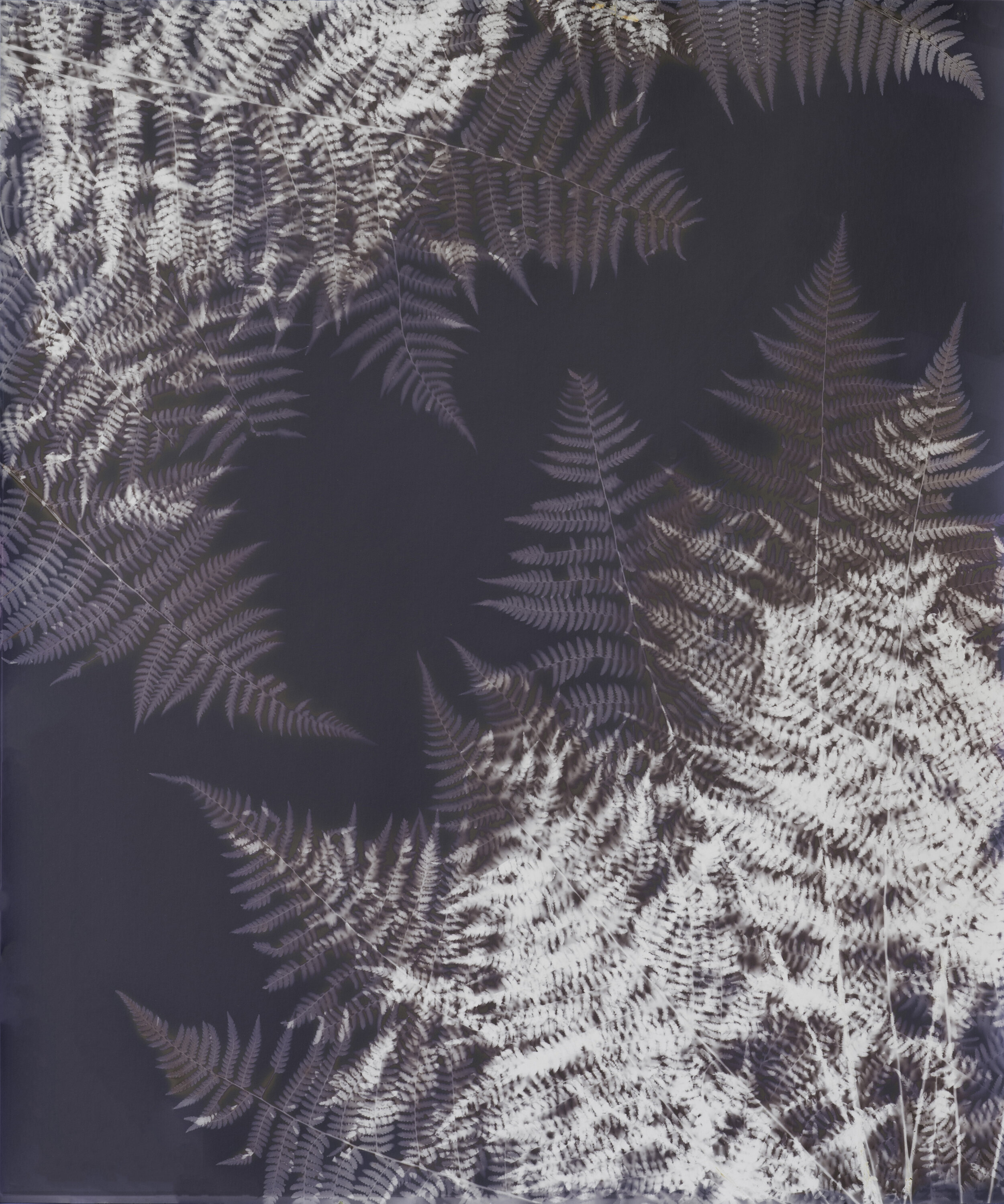

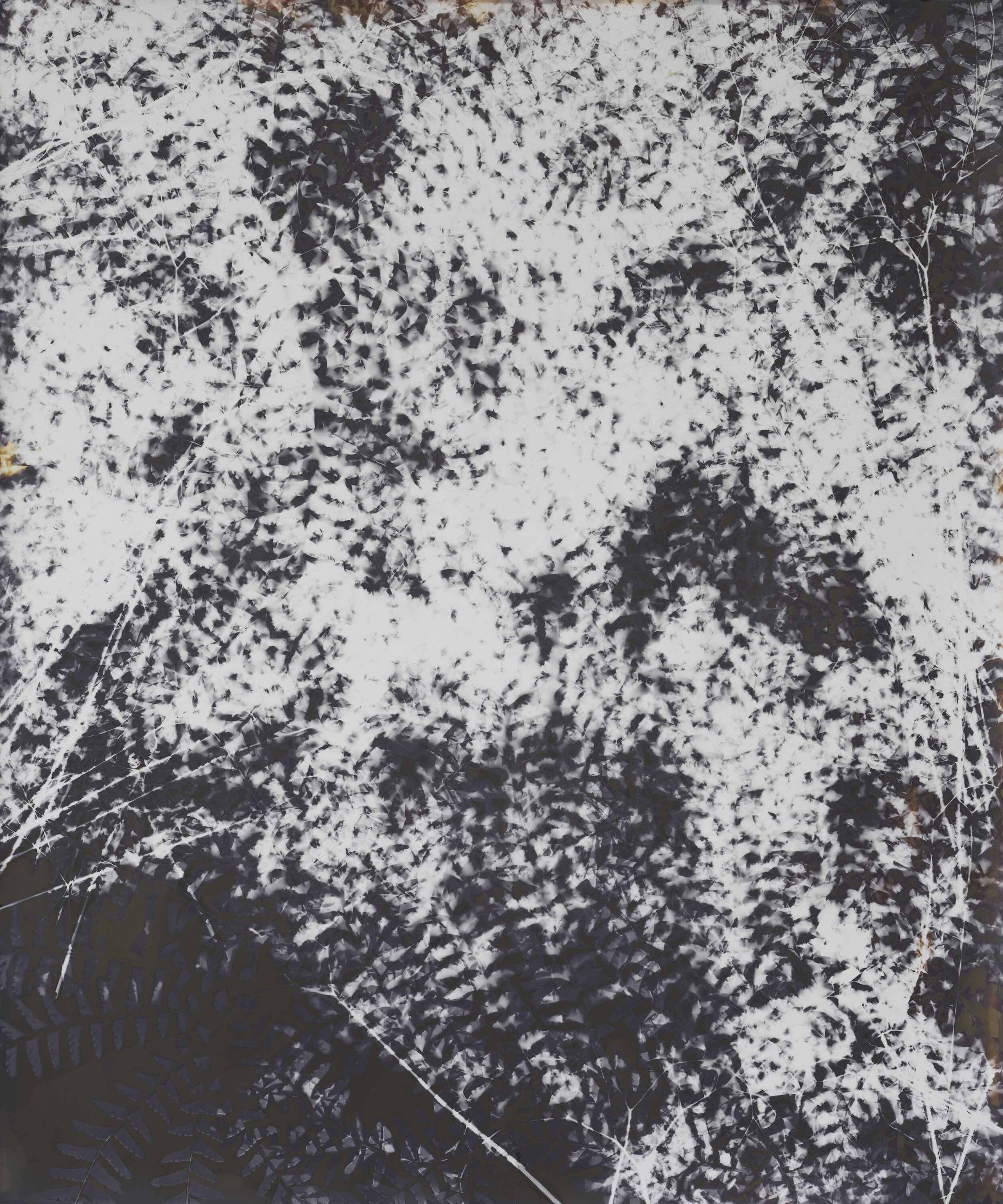

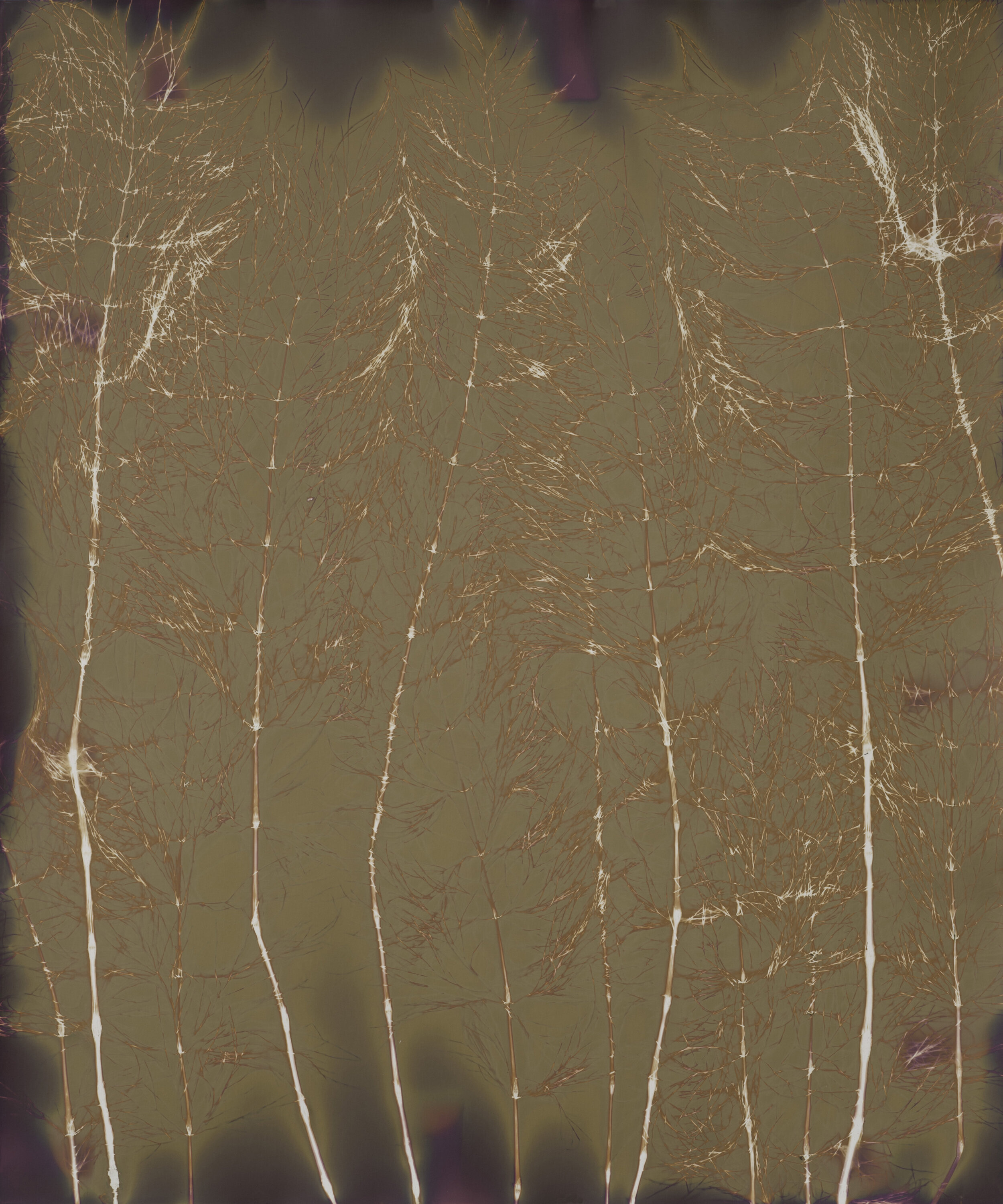

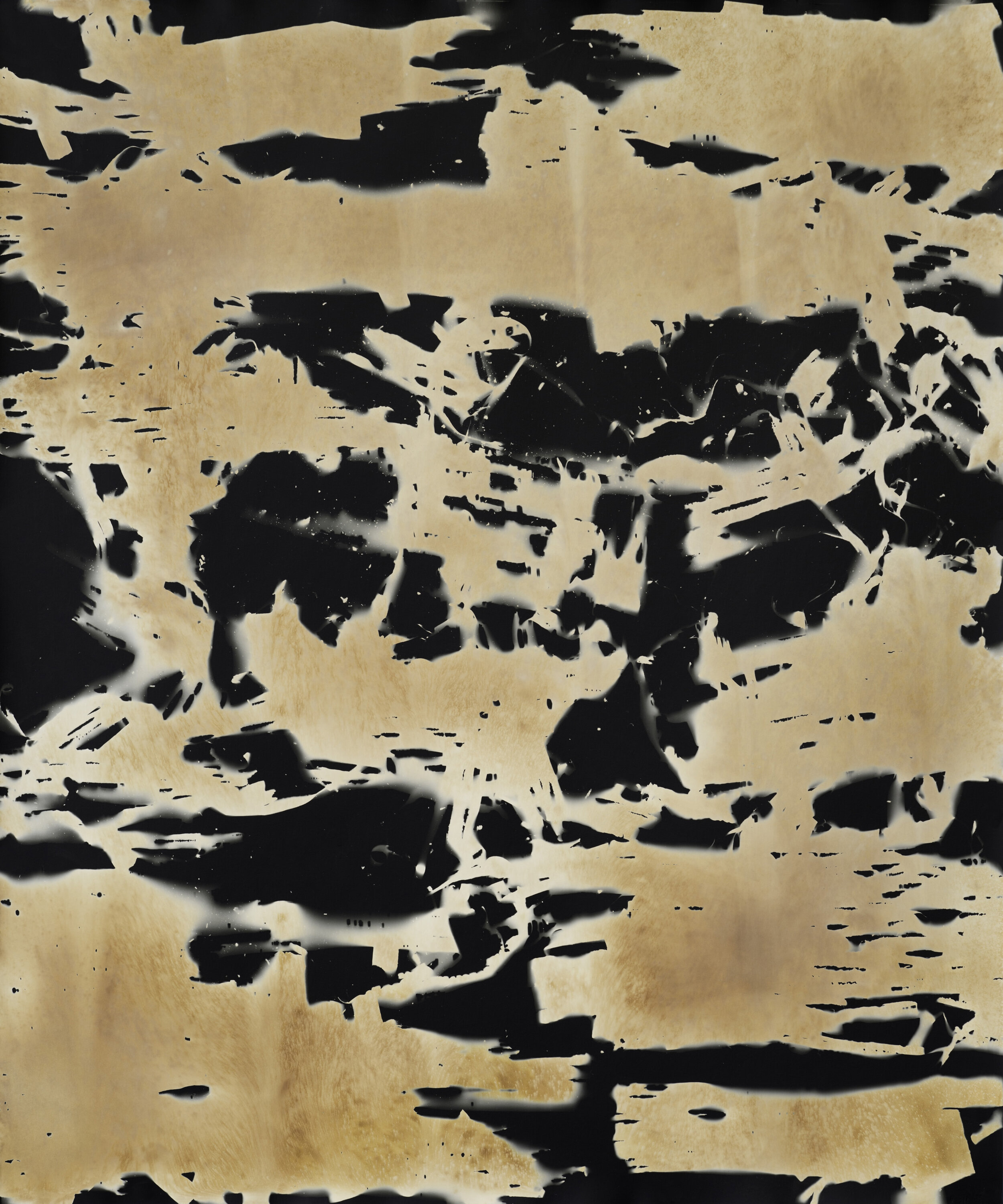

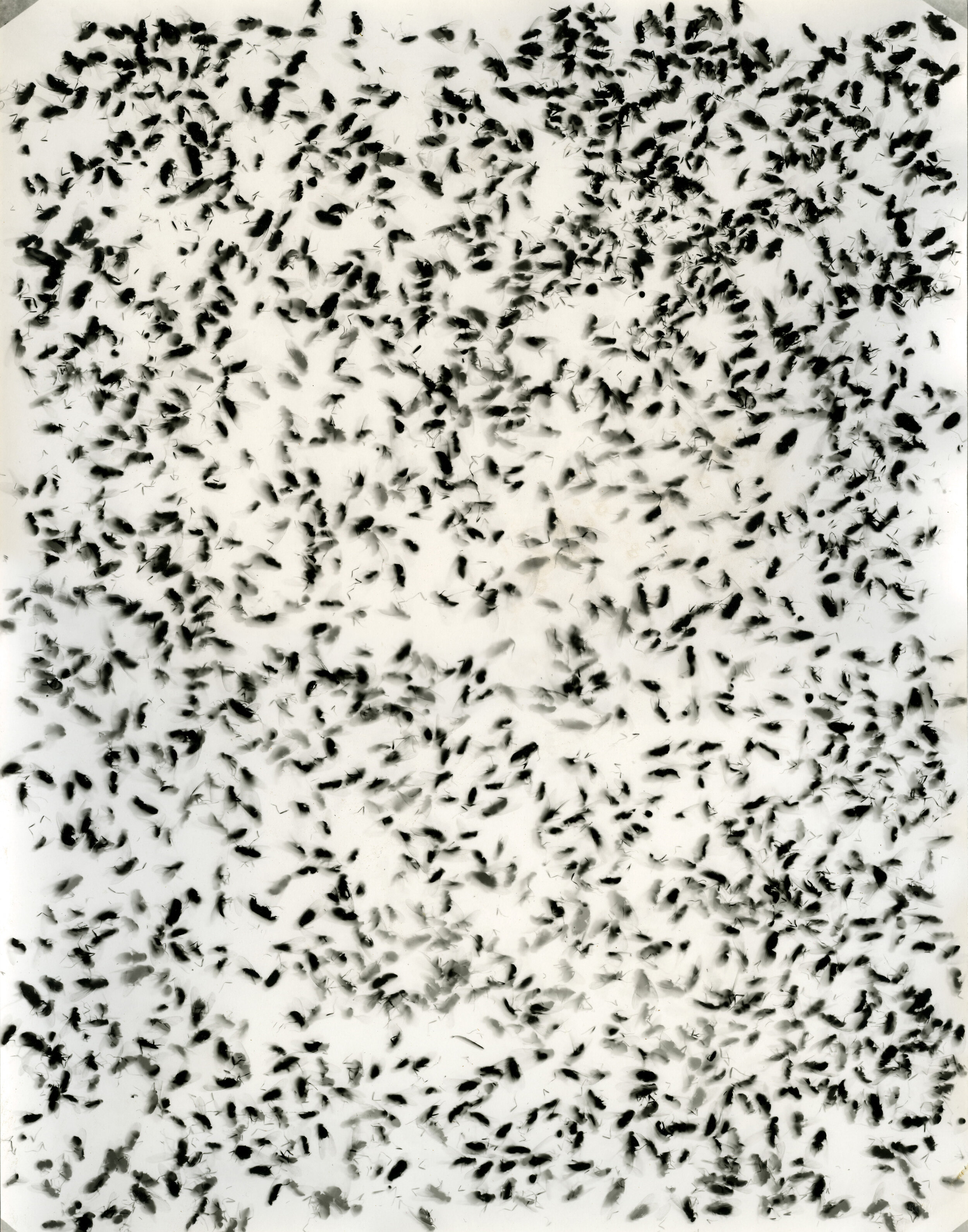

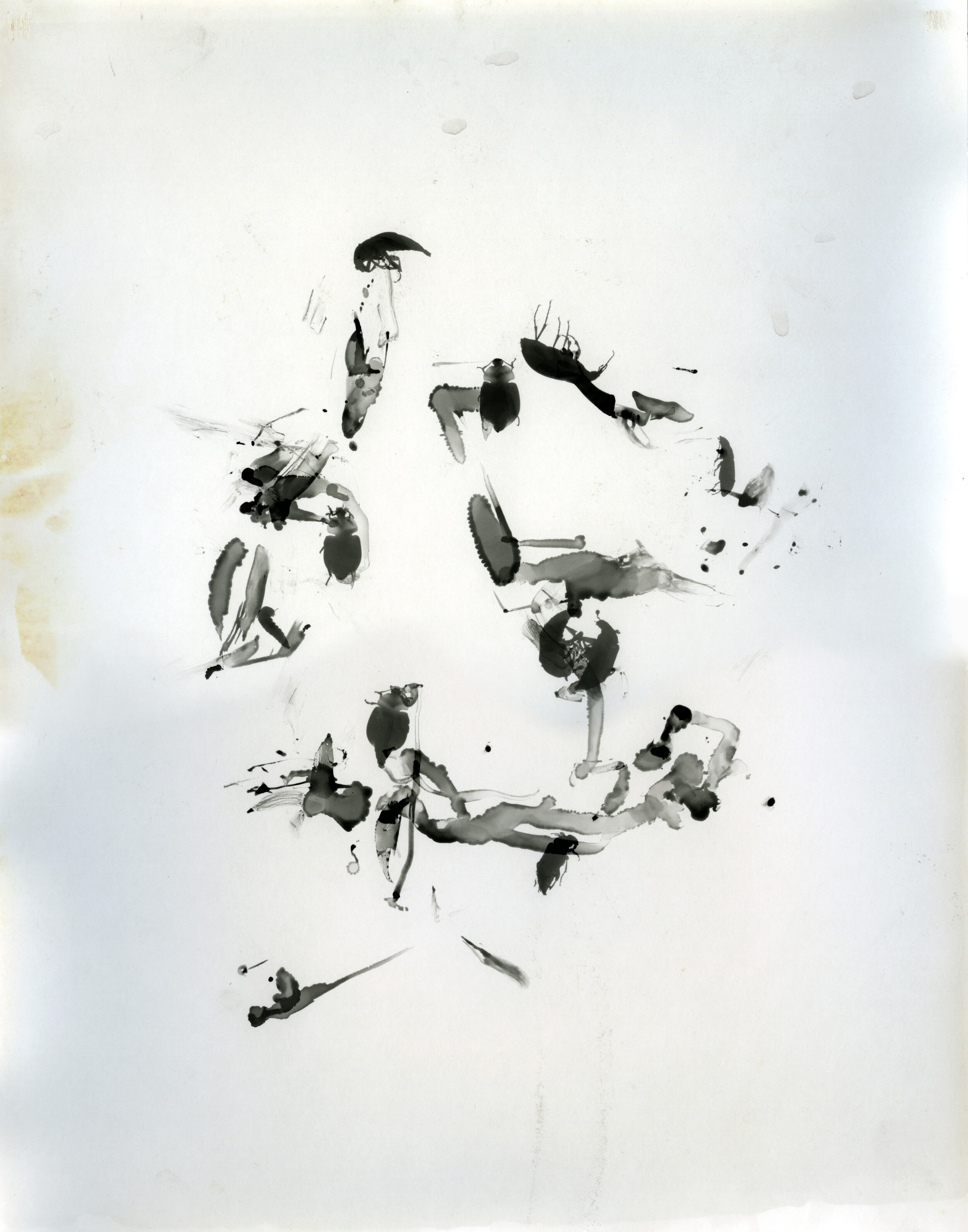

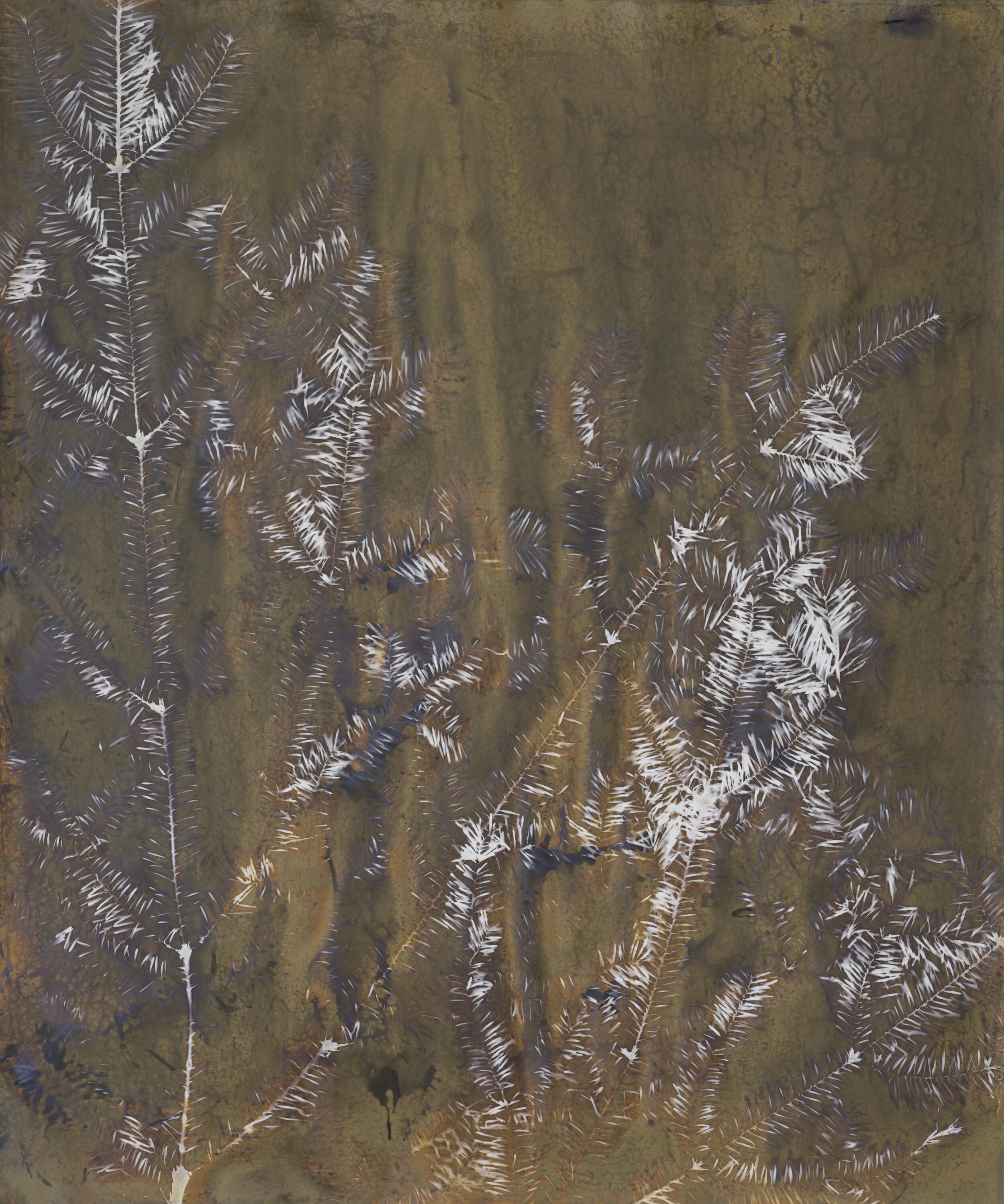

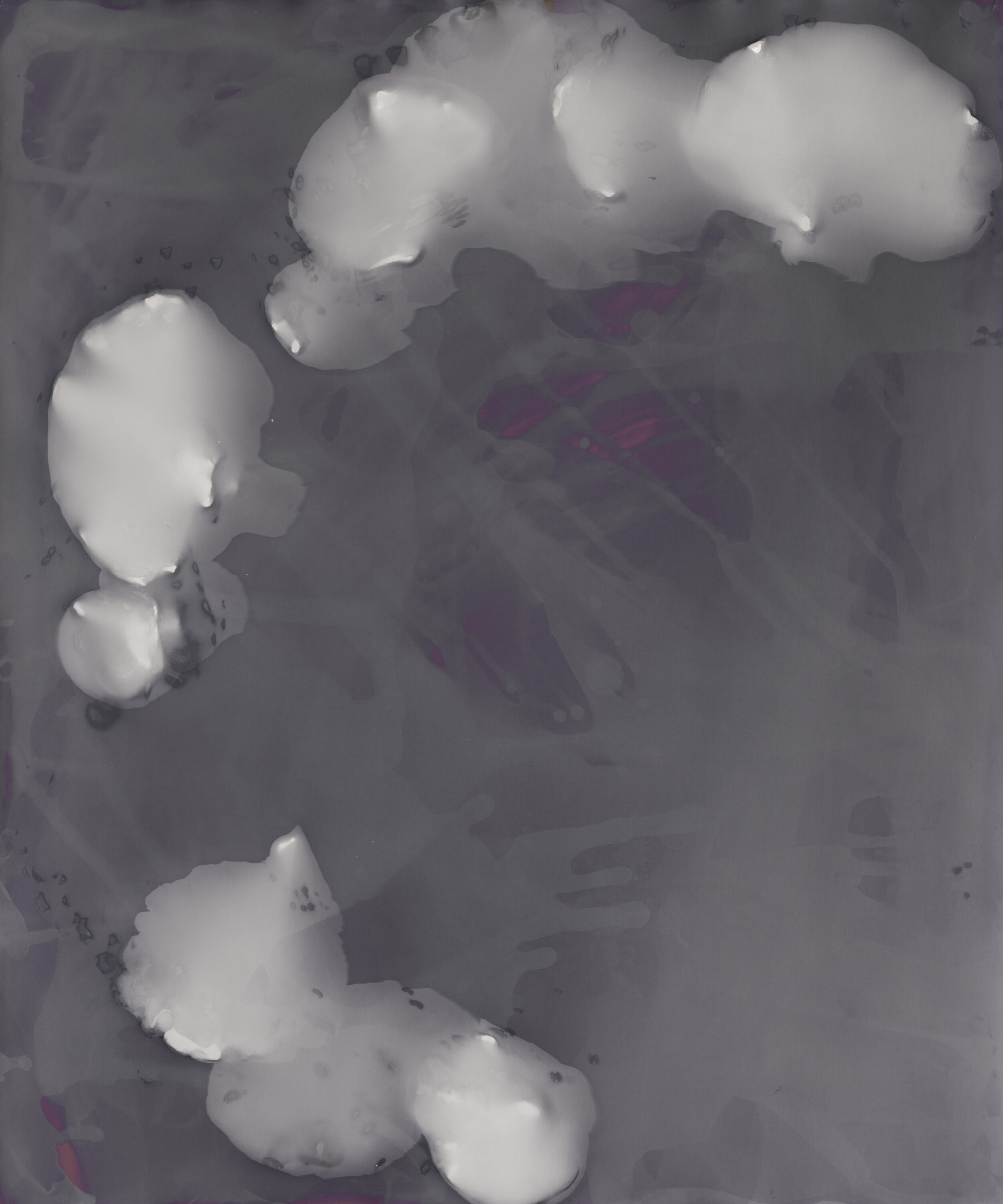

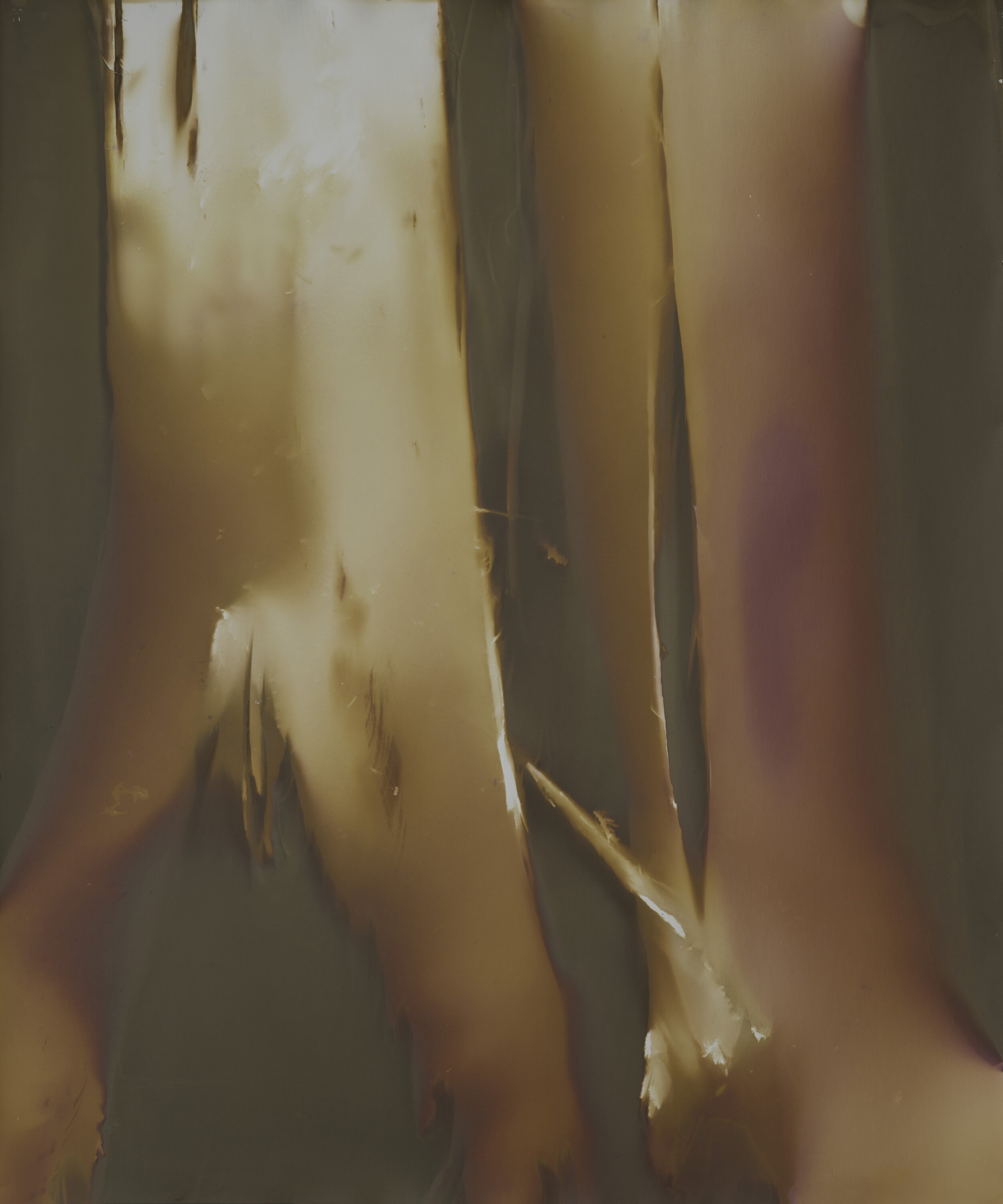

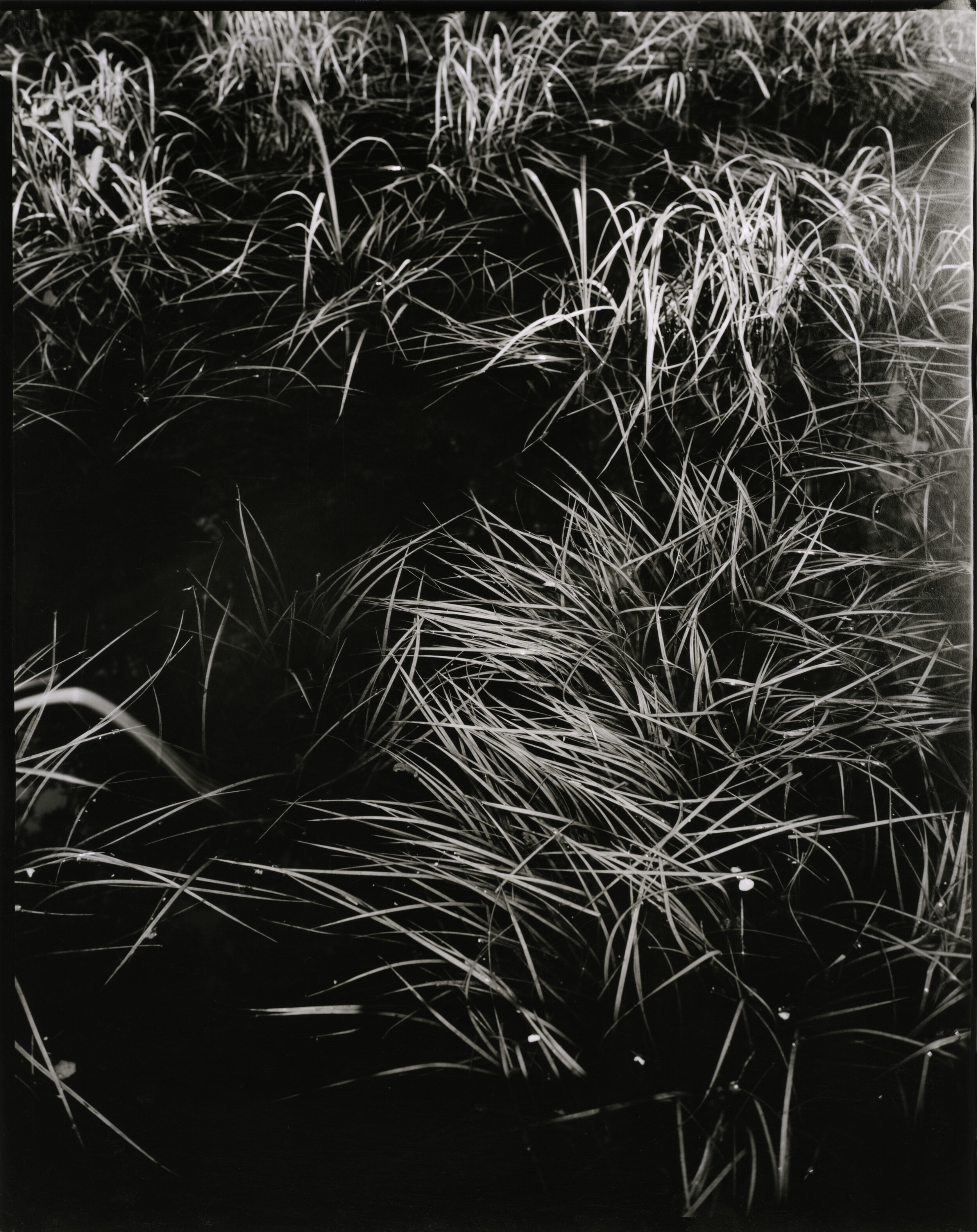

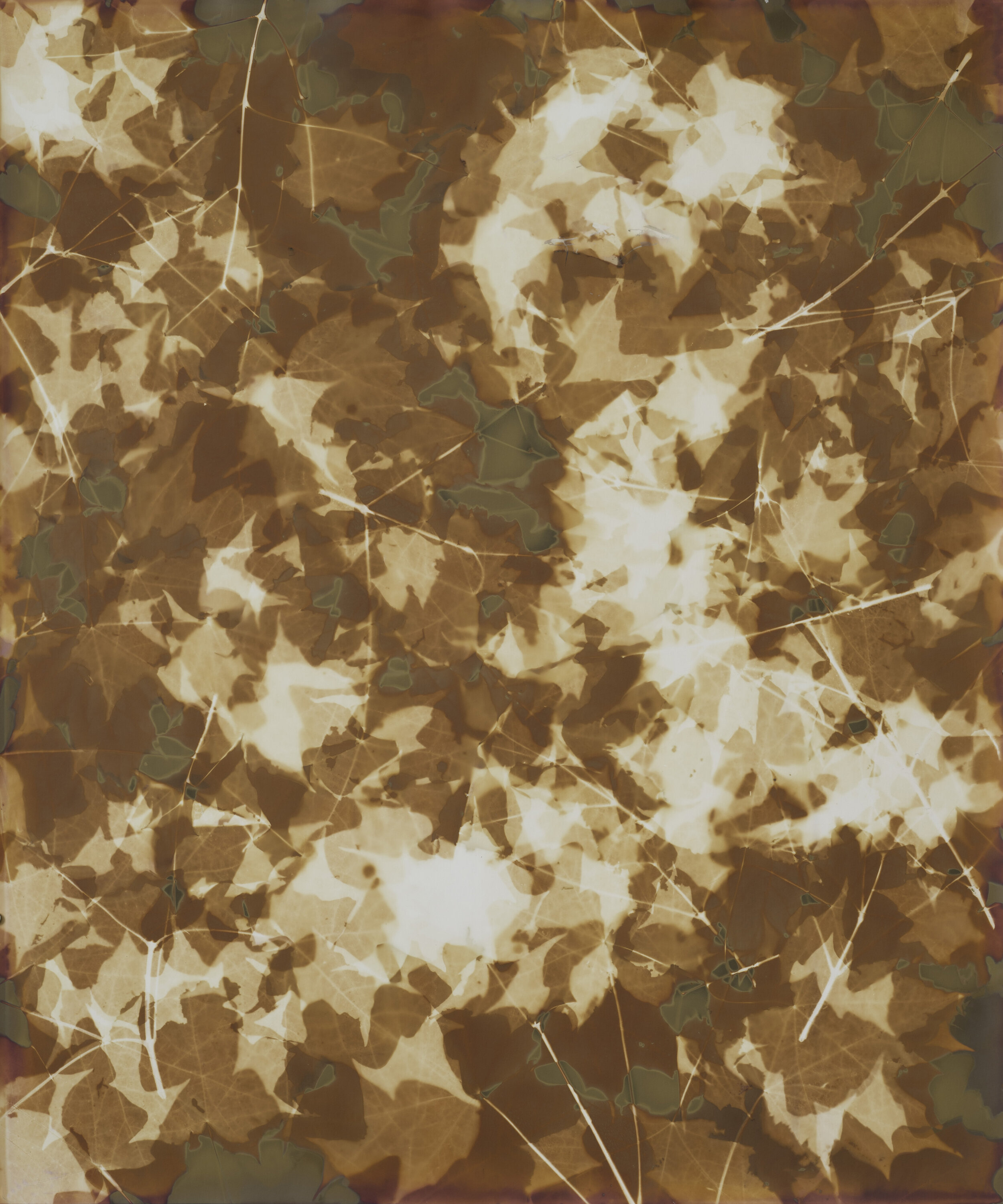

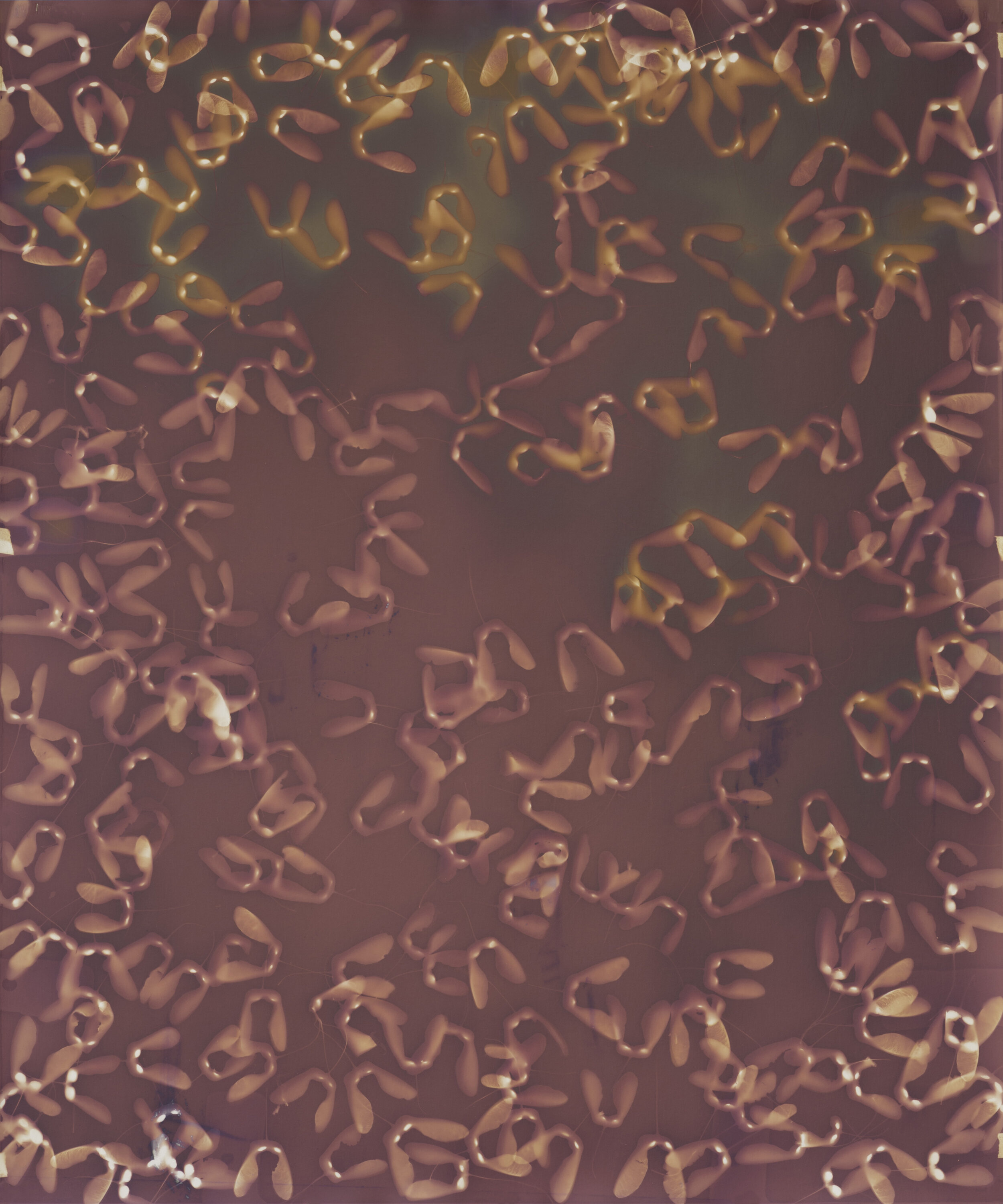

In June 2018 I was an artist-in-residence at the University of Notre Dame Environmental Research Center in the remote woods of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. While I was there I created a series of lumen prints and photograms: camera-less photographic prints made by placing objects (plants, insects, fungi, etc.) on silver-gelatin photo paper, exposing them to sunlight, and in some cases toning them with chemicals. The results are painterly, semi-abstract images that emphasize the physicality of the photograph.

As I walked through the North Woods and talked with scientists at UNDERC, I discovered even that ostensibly “pristine” wilderness is dramatically impacted by human activities. For example, wolves were hunted out long ago, and without them deer are left to overgraze many understory plants, leaving nothing but ferns instead of a wealth of botanical diversity. The title Refugia comes from a term ecologist Walter Carson uses to describe places the deer can’t reach. He studies these “refuges” to determine what the plant life should look like without as many deer.

This body of work references early photographers, especially Anna Atkins and William Henry Fox Talbot, both of whom used botanical specimens in their photographic experiments. However, Atkins’s and Talbot’s compositions are neat and orderly, reflecting a 19th century scientific sensibility. Mine are chaotic, evoking chance reactions and unpredicted consequences. In spite of their lush colors and ghostly beauty, mine are images of the uncertainty facing our environment in the 21st century.